TRADOS and SDL joined together in April 2005 to strengthen and better serve the globalisation ecosystem – the strong relationship among all players in the translation process bound by a common technology. The management said at that time:

We will provide you with more valuable and powerful products solutions that are more cost-effective and enable you to be more productive in less time. Not only will the merger lead to more valuable and powerful products, but we can also provide them with a lower cost of total ownership…

The Background: SDL Buys TRADOS

In a deal with far-reaching implications, publicly-traded SDL International (SDL) announced on 20 June 2005 that it would buy privately-held TRADOS Inc. for US$60 million. When its shareholders approved the purchase in early July, SDL became by far the largest supplier of translation memory, terminology management, and translation workflow management products. SDL is also one of the world’s three largest language services providers (LSP). SDL’s purchase of TRADOS created a larger company that is more visible to a broader range of buyers dealing with global or multilingual application and content development.

This deal created by far the largest globalisation technology company. Publicly traded SDL’s 2004 revenue was roughly $114 million at today’s exchange rate (GBP62.7 million), while privately held Trados reportedly turned over more than $25 million. SDL directly invoiced about $5 million in software sales, although it claims that upwards of 50% of its revenue is technology-driven. This deal has created an independent software vendor that directly booked more than $30 million in globalization tool business in the first year after the acquisition.

This acquisition had some critics: Trados had been the Switzerland of translation memory, terminology management, and translation workflow, offering the only independent desktop-to-enterprise solutions. The only other one-stop-shops were SDL and the Star Group, both companies that would happily sell you tools AND language services. Some rival translation agencies didn’t like buying core software from SDL or Star, but in this consolidating world, they won’t have much of a choice unless someone with deep pockets comes along to meld the best of the independent, point-solution translation memory, termbase, and workflow solutions into a single offering. Trados CEO Joe Campbell joined the SDL Board of Directors. Recruited from content management player iManage when it was acquired by Interwoven, Campbell added CMS expertise to SDL’s plans for a leading role in the global information management business.

Language Industry Background

This purchase by SDL continued a previously begun round of consolidation in the language services and tools industry, including Lionbridge’s proposed purchase of BGS. That deal created the world’s largest LSP with annual revenue exceeding US$400 million. Other 2005 deals of note included Irish LSP Transware ‘s purchase of globalisation management system supplier GlobalSight and Merrill acquisition of P.H. Brink, both acquiring translation workflow management tools in the transactions. The SDL and Lionbridge deals, though, captured most attention due to their size.

- SDL buys TRADOS. SDL bought TRADOS for US$60 million (2.5 times TRADOS’ revenue), becoming the largest supplier of translation memory, terminology management, and translation workflow management products. SDL’s combined language service and tool revenue for 2004 was $114 million (£62.7 million), while TRADOS earned over $25 million selling tools and related services. Combined, the two companies account for the lion’s share of translation memory and translation workflow management software sale.

- Executives highlighted SDL’s mission to meet the “global information management” needs of large enterprises in both technology and language services. Its bigger technology portfolio, more best practices and methodologies, increased economies of scale, and amplified marketing energy gave it a more strategic role in the entire information life cycle from authoring to localisation to publishing.

- Lionbridge’s acquisition of Bowne Global Solutions. Lionbridge paid US$180 million for BGS, becoming the world’s largest LSP with this deal. In 2004, BGS booked $223 million in revenue compared to Lionbridge’s $154.1 million. The purchase price worked out to 80 percent of BGS’s 2004 revenue.

- Executives emphasized scale, noting the increased ability to provide services across the entire application and content development life cycle, the cost-effectiveness of farming out labour to low-wage countries like India and the increased geographic footprint that BGS brings to the company.

Why Who Owns the Tools Is Important

Nearly nine out of ten companies outsource their translation and localisation work to language service providers. Buyers can choose from a wide variety of LSPs around the world, all falling into one of three categories when it comes to the technology they use to translate, localise, and manage customer projects.

- The LSP buys most of its technology. These companies purchase translation memory workbenches, perhaps preferring one supplier but realistically using whatever the client wants. Many layer project management and workflow applications on commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) products such as Microsoft Access or Project . Earlier this year BGS had announced that it would join this camp, standardizing core elements of its production process on TRADOS-supplied software. However, the company did not execute on this plan as TRADOS sold itself off to SDL.

- The LSP builds some tools, but keeps them to itself. Some firms like Connect Global , EQHO Communications , and Merrill Brink International build software infrastructure and tools that meet their specific needs better than any COTS product would. Lionbridge is the most visible example of such a company, assembling its infrastructure from commercially available and proprietary components. Earlier this year it purchased Logoport , a small software firm selling a web-based translation memory tool. A side-benefit of controlling its TM fate is that Lionbridge avoids having to buy licenses from SDL or TRADOS for the clients who don’t care which TM it uses.

- The LSP builds technology and sells it to all comers. A few providers sell software, tools they developed (or acquired) to meet their internal needs for project management and technology needs. They hope to recoup their investment by selling them on the open market. SDL, STAR , Translations.com , and Transware exemplify this model. This approach pleases shareholders by turning a cost of doing business into an asset, but it does limit the marketability of the tools because many LSPs feel uncomfortable buying core technology from a rival. This last point is at the heart of the concerns expressed by GALA members and inspired the survey.

This purchase was only a step in the global consolidation of the language services and tools industry. Within the same year, Lionbridge (US) bought Logoport (Germany), Transware (Ireland) bought GlobalSight (US), and Bowne Global (US). These mergers and acquisitions have affected buyers who can expect to have their business solicited by rival players, who will re-align their partnerships to match the new polarities of the industry, and venture capitalists and other investors might wake up to some potential opportunities. The one thing we don’t see is regulatory agencies in the United States or the European Union getting involved over the potential monopolisation of the translation memory industry — these companies are still too small for anyone in Washington or Brussels to take notice.

all of your necessary information in a single place, which increases your chances of finishing the project on time and, more importantly, within budget.

all of your necessary information in a single place, which increases your chances of finishing the project on time and, more importantly, within budget.

In an age in which we are seeing more and more things automated everyday, we still rely on a human element for completing high quality translation activities. Even with AI advancements, we are still a while off before transcription jobs can be done completely and successfully without human input.

In an age in which we are seeing more and more things automated everyday, we still rely on a human element for completing high quality translation activities. Even with AI advancements, we are still a while off before transcription jobs can be done completely and successfully without human input.

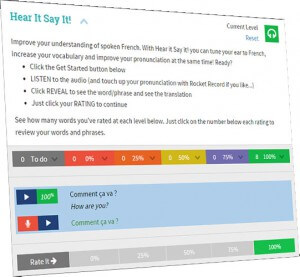

Did you know that French is the second most learned language after English? And, it’s the ninth most widely spoken language around the globe, in fact there are over 200 million people spanning 5 major continents who speak the language.

Did you know that French is the second most learned language after English? And, it’s the ninth most widely spoken language around the globe, in fact there are over 200 million people spanning 5 major continents who speak the language.

Legal Documents

Legal Documents

found out a few years back, when misleading Spanish instructions on bilingual labels forced it to recall 4.6 million cans of Nutramigen Baby Formula. Following the flawed directions could have caused illness or even death, said company officials.

found out a few years back, when misleading Spanish instructions on bilingual labels forced it to recall 4.6 million cans of Nutramigen Baby Formula. Following the flawed directions could have caused illness or even death, said company officials.

Could This Be You?

Could This Be You?